It was in December 1881 that a novel solution to the problem was first given a public airing.

The Lynton and Lynmouth Recorder received a letter, signed only with the nom de plume Pro Bono Publico, proposing: A tramway between the two towns to be worked by a stationary engine at Lynton, the motive power being taken from the river Lyn, put in tanks on rolling carriages and these let down the tramway under proper control.

The weight of the water going down would, with the application of simple machinery, bring up anything that might be desired up from Lynmouth.

The letter offered a solution to the problems of transporting both freight and people up and down the cliff, but such a scheme would require a large capital investment, so for some years it remained nothing more than a talking point.

Late in 1885, two very different men co-promoted the scheme. John Heywood, a self-made local businessman, and Thomas Hewitt, a distinguished London lawyer with a residence at The Hoe on Lynton’s North Walk, proposed a major project which included the construction of a solid pier, an esplanade and ‘a lift from the said pier or promenade to Lynton’. Hewitt used his legal skills to guide a bill through Parliament.

The pier, to extend 112 yards into the sea, was intended to enable the resort to attract a bigger share of the growing steam-excursion traffic.

Many of the paddle steamers had not been calling at Lynmouth where passengers had to be ferried ashore in small boats, instead visiting Ilfracombe where tourists could easily disembark at the deep-water pier.

The construction of an esplanade, which survives today, was to start from a point near the Rhenish Tower and provide access to the pier.

The proposed ‘lift’ would make it possible to carry up to Lynton the large numbers of people that would be landed from the steamers at the new pier.

By October 1886, the ‘Lynmouth Promenade, Pier and Lift Provisional Order’ had received official sanction.

John Heywood was Chairman of the Lynton Local Board and fact that he also had a financial interest in the scheme did not stop him using his influence to persuade the members of his local government to spend ratepayers’ money building the first part of the esplanade.

It would be argued that John Heywood was a public-spirited man who believed his project would bring great prosperity to the local community.

Yet it was clear that he was an astute businessman who had already acquired the Lime Kilns and all the gardens and fields adjoining the proposed promenade and that these sites could be expected to rise rapidly in value if the project were completed.

The first part of the esplanade, running 165 yards westwards from the Rhenish Tower, opened in September 1887.

In the same month, the lawyer, Thomas Hewitt, invited his friend George Newnes, the wealthy publisher of Tit Bits Magazine, to be his guest at The Hoe.

It seemed quite possible that, by this time, Hewitt had realised that the construction of the cliff railway would require more capital than he and Heywood had available and that he hoped to persuade Newnes to invest in the project.

What is certain, is that within 24 hours of arriving at The Hoe, Newnes had agreed to provide most of the money for a cliff railway.

“Is there anyone in the place capable of constructing such a railway?” George Newnes asked. Yes, there is such a man, he was informed, Bob Jones.

Newnes asked that he be told to call as soon as possible. Newnes later wrote of his first meeting with the engineer: “That evening, we fixed up a plan by which we could make a cliff railway. I took the rest in hand”.

This was the way George worked. He saw an opportunity and seized it. Schemes which met a public need and yet were likely to make him a handsome profit appealed to him.

He agreed to provide most of the capital, but Bob Jones and Thomas Hewitt also invested in the project and became fellow directors.

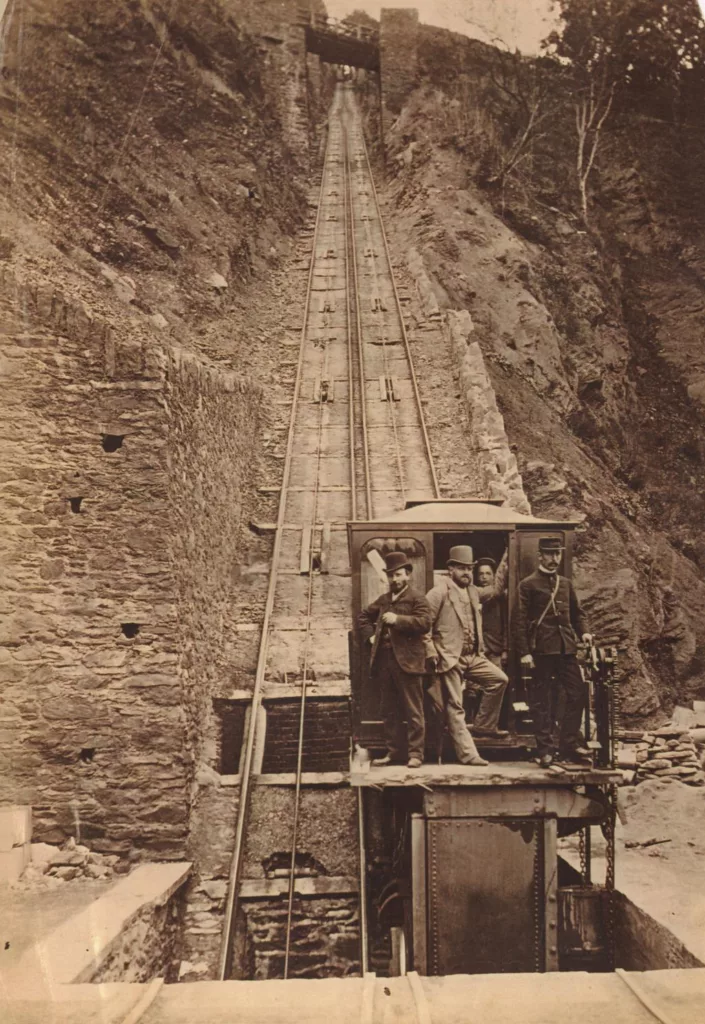

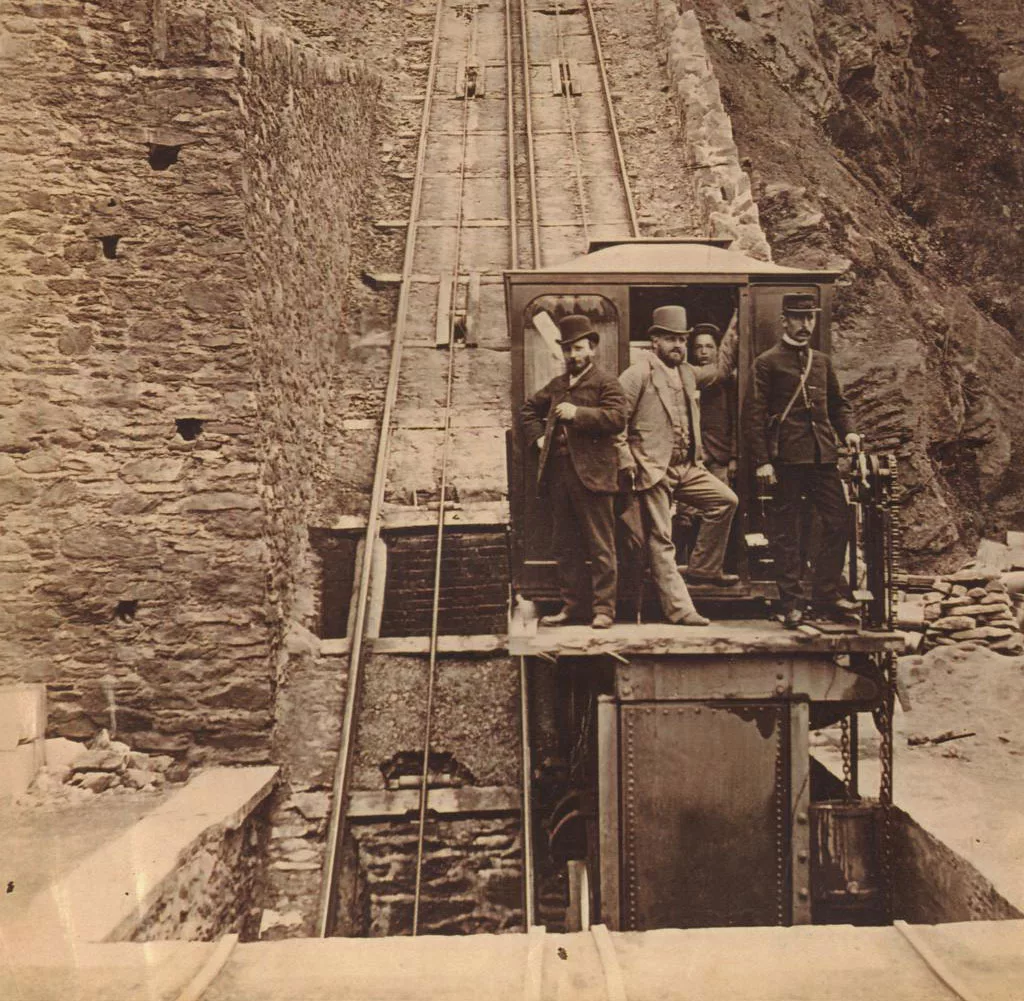

Due to the extreme length of the proposed railway, (some 900 feet) rising over 500 feet vertically at an incline of 1:1.75, the safety aspect, particularly the braking system would have to be far more advanced than those normally used on funicular lifts. Bob Jones suggested his relative, George Croydon Marks, an engineer with the particular skills set and George was quickly appointed.

Marks decided on 4 separate systems. Two were to be friction brakes, sets of steel blocks that are pressed down on to the crown of the rail by hydraulic pistons.

The remaining two systems, which would constitute the main system, were to be hydraulic callipers, which clamped across the crown of the rails.

This system was eventually patented in the names of Newnes, Jones and Marks in 1888.

Blasting operations soon took place on the cliff. By December The North Devon Journal could report: “The excavations for the purpose of a hydraulic lift between Lynton and Lynmouth is steadily progressing. Many thousands of tons of material have been removed from the hillside”.

The Cliff Railway was finally opened on Easter Monday (the 7th April) in 1890. A large crowd gathered at the Lynton station to see Mrs Jeune, Lady of the Manor of Lynton, perform the official ceremony.

George Newnes conducted her to a raised dais under the wall of the reservoir from which the cistern of the car would be filled.

After receiving a bouquet of flowers from Bob Jones’ little daughter, Mrs Jeune pulled a lever releasing the first car which began its first descent, whilst the second car simultaneously started its upward journey.

If you’d prefer not to sign up, but would still like a copy of the brochure, contact us here.

© 2025 Lynton & Lynmouth Cliff Railway